Building Your Color Palette

Adapted from our book and video series, Refactoring UI.

Ever used one of those fancy color palette generators? You know, the ones where you pick a starting color, tweak some options that probably include some musical jargon like "triad" or "major fourth", and are then bestowed the five perfect color swatches you should use to build your website?

This calculated and scientific approach to picking the perfect color scheme is extremely seductive, but not very useful.

Well, unless you want your site to look like this:

What you actually need

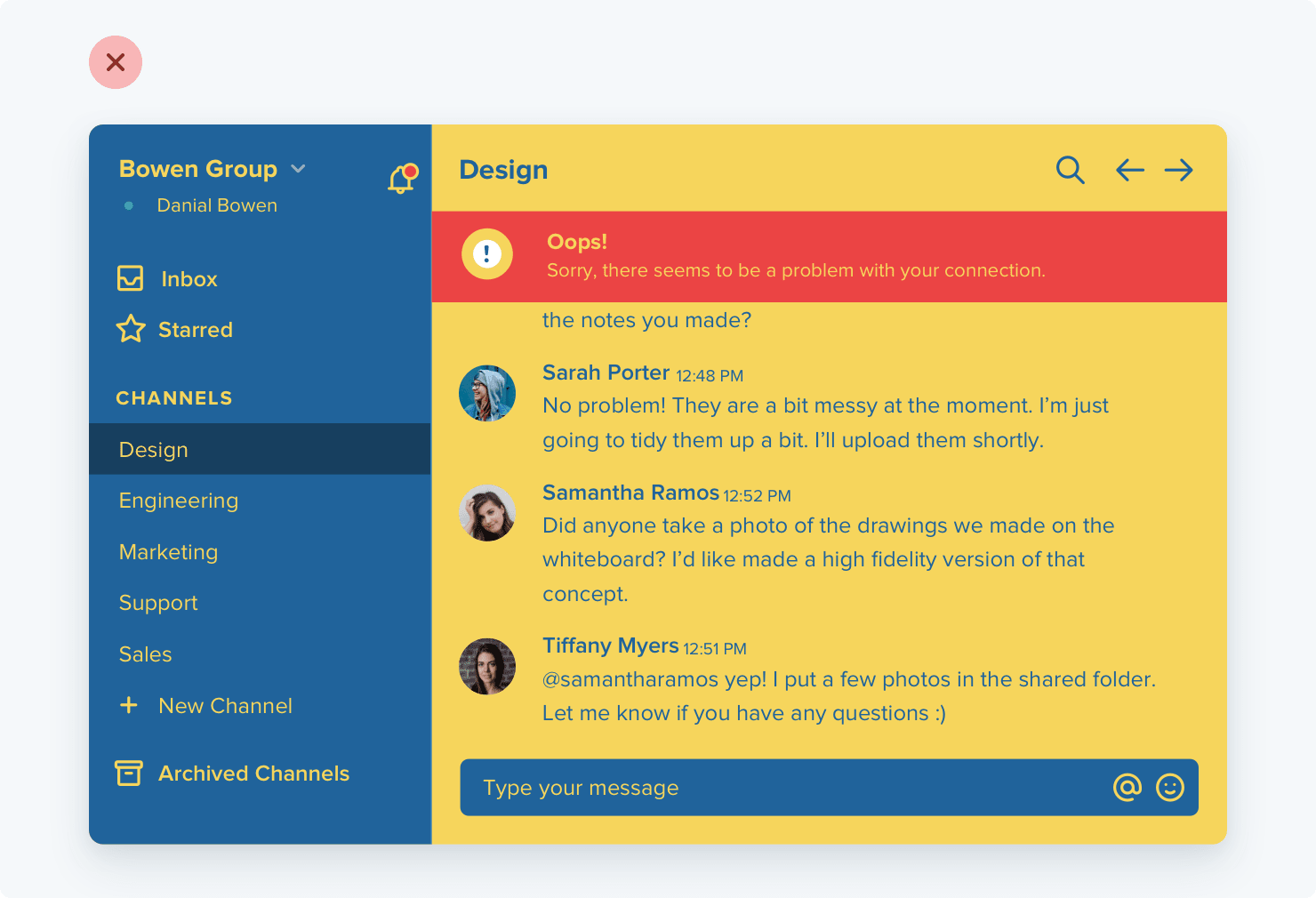

You can't build anything with five hex codes. To build something real, you need a much more comprehensive set of colors to choose from.

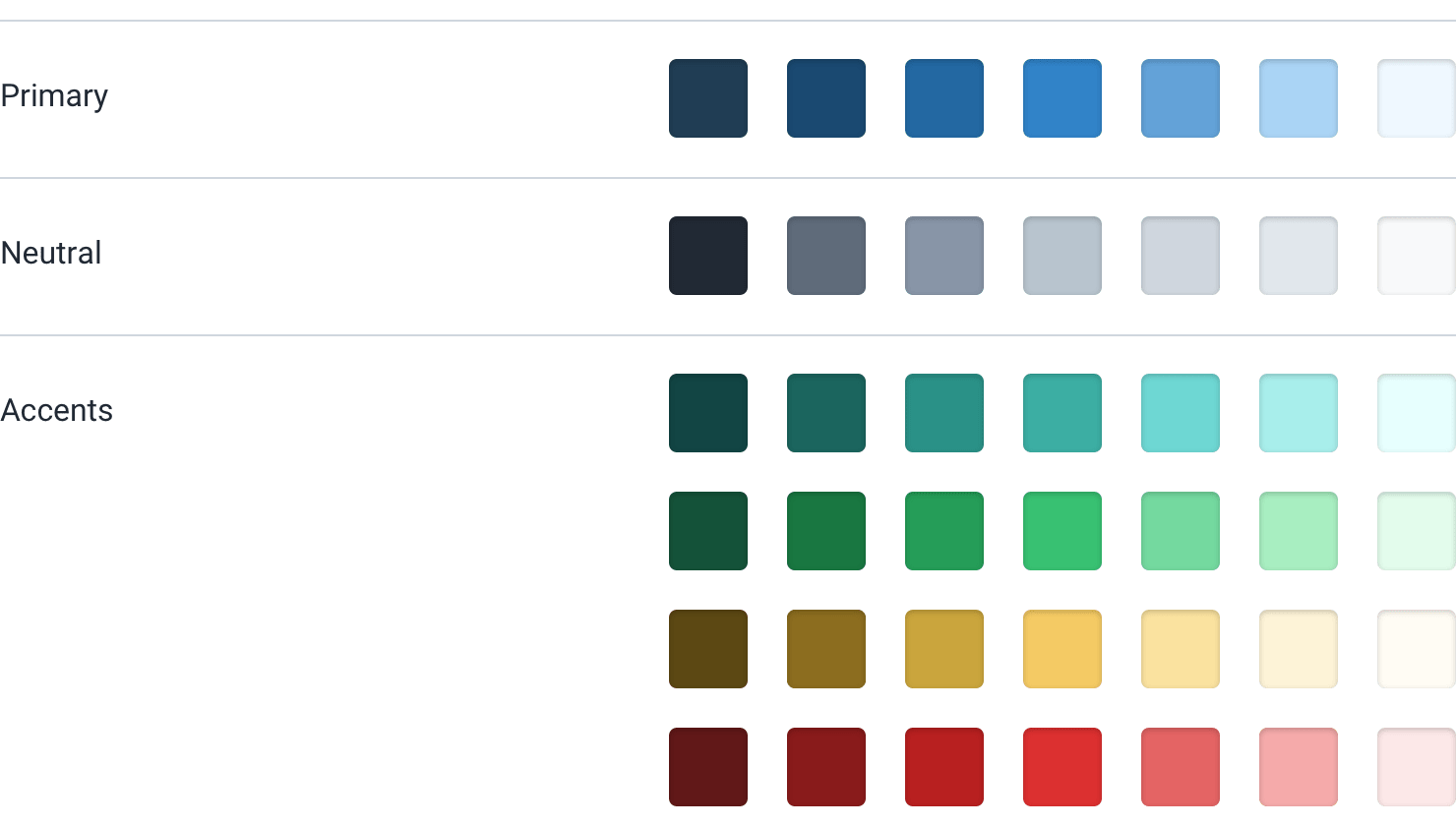

You can break a good color palette down into three categories.

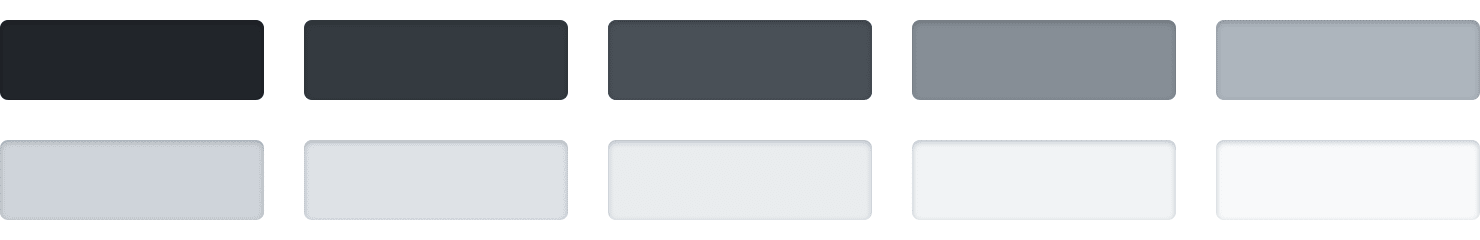

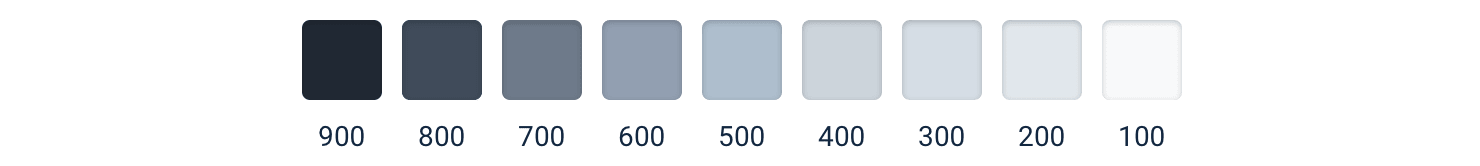

Greys

Text, backgrounds, panels, form controls — almost everything in an interface is grey.

You'll need more greys than you think, too — three or four shades might sound like plenty but it won't be long before you wish you had something a little darker than shade #2 but a little lighter than shade #3.

In practice, you want 8-10 shades to choose from (more on this later). Not so many that you waste time deciding between shade #77 and shade #78, but enough to make sure you don't have to compromise too much .

True black tends to look pretty unnatural, so start with a really dark grey and work your way up to white in steady increments.

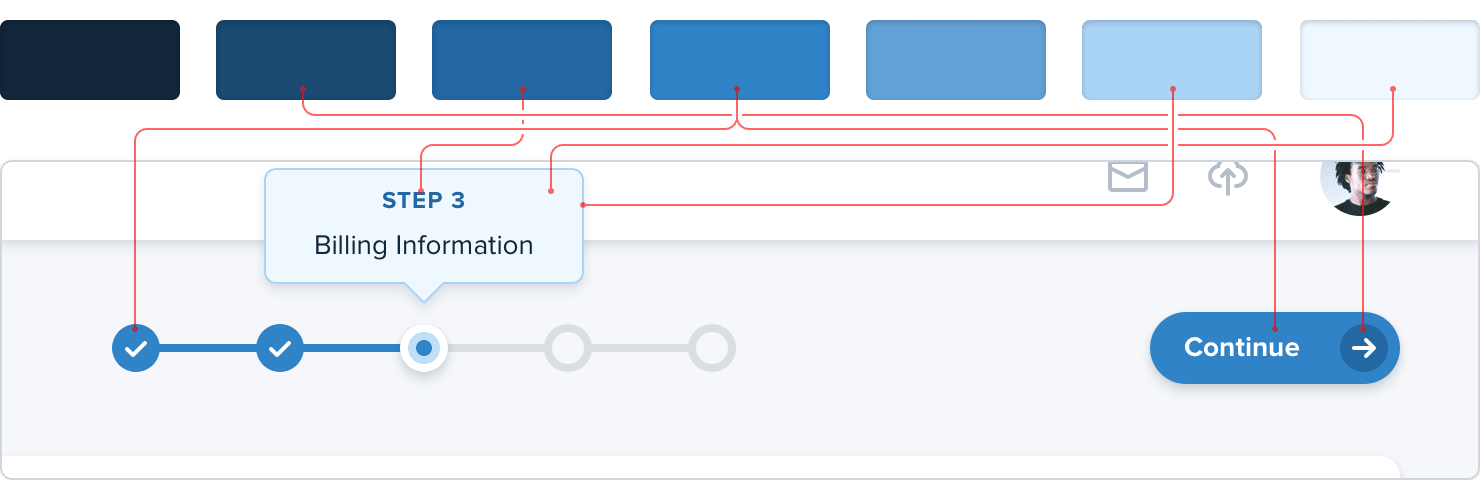

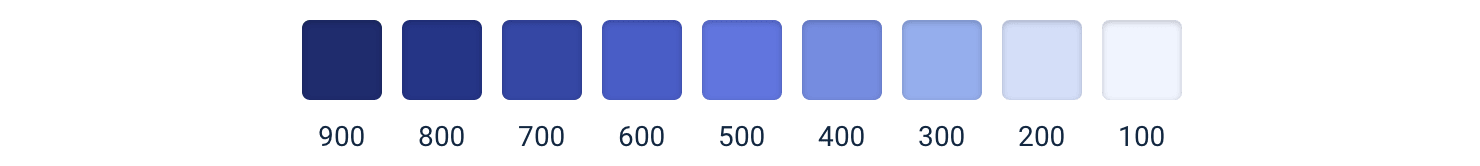

Primary color(s)

Most sites need one, maybe two colors that are used for primary actions, emphasizing navigation elements, etc. These are the colors that determine the overall look of a site — the ones that make you think of Facebook as "blue", even though it's really mostly grey.

Just like with greys, you need a variety (5-10) of lighter and darker shades to choose from.

Ultra-light shades can be useful as a tinted background for things like alerts, while darker shades work great for text.

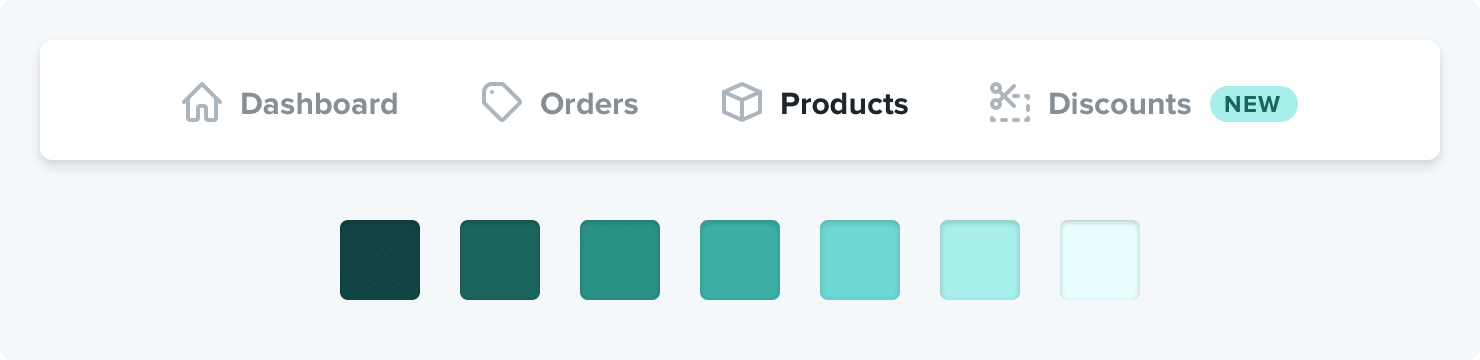

Accent colors

On top of primary colors, every site needs a few accent colors for communicating different things to the user.

For example, you might want to use an eye-grabbing color like yellow, pink, or teal to highlight a new feature:

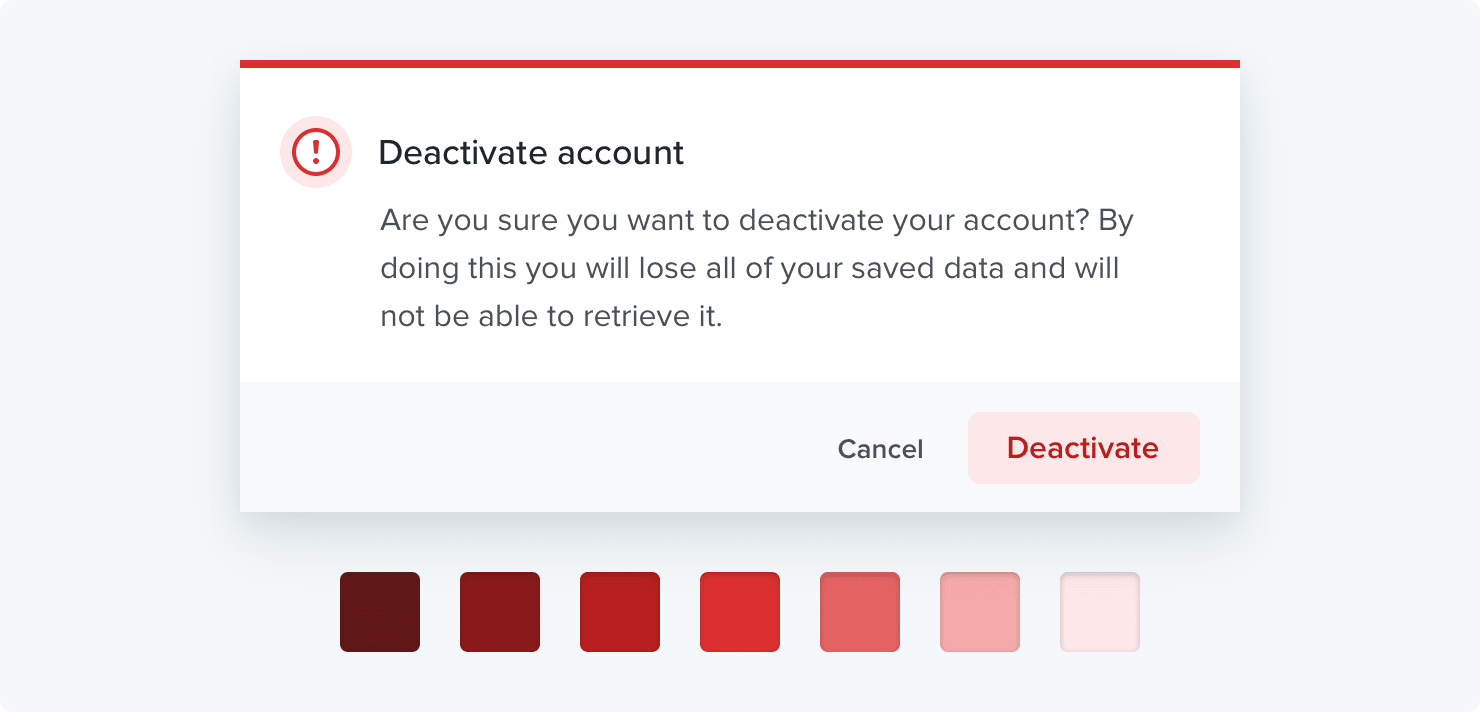

You might also need colors to emphasize different semantic states, like red for confirming a destructive action:

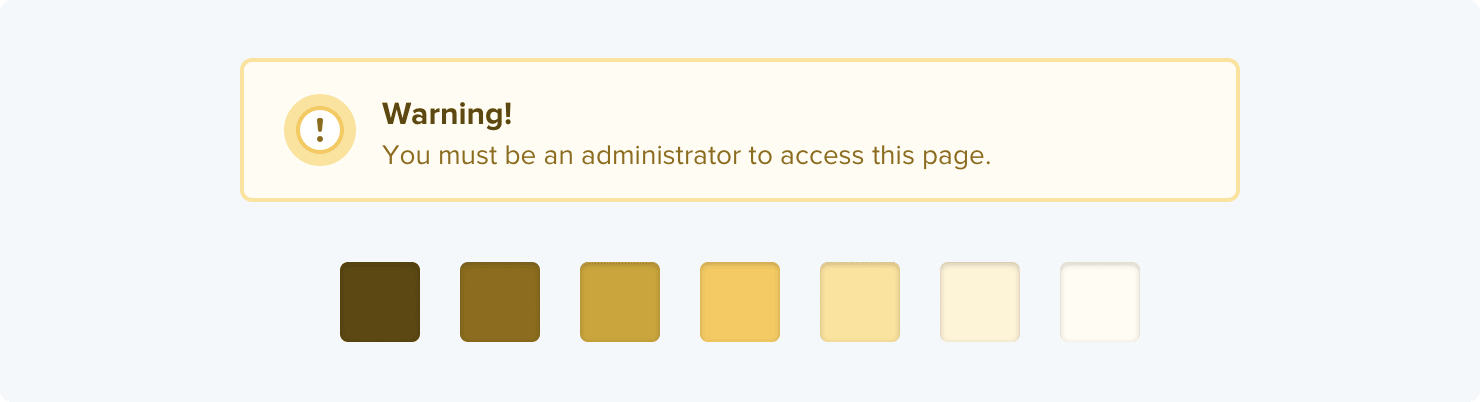

...yellow for a warning message:

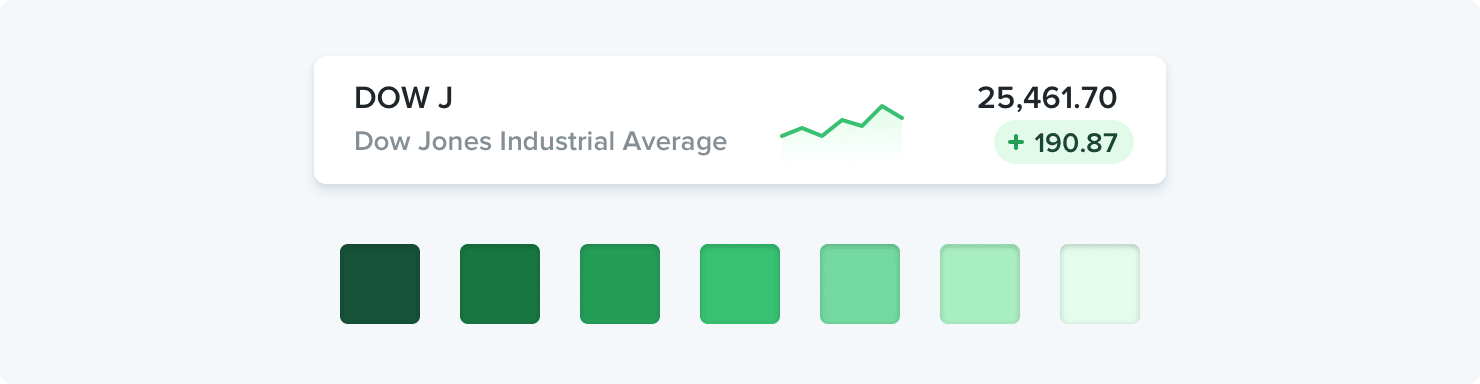

...or green to highlight a positive trend:

You'll want multiple shades for these colors too, even though they should be used pretty sparingly throughout the UI.

If you're building something where you need to use color to distinguish or categorize similar elements (like lines on graphs, events in a calendar, or tags on a project), you might need even more accent colors.

All in, it's not uncommon to need as many as ten different colors with 5-10 shades each for a complex UI.

Define your shades up front

When you need to create a lighter or darker variation of a color in your palette, don't get clever using CSS preprocessor functions like "lighten" or "darken" to create shades on the fly. That's how you end up with 35 slightly different blues that all look the same.

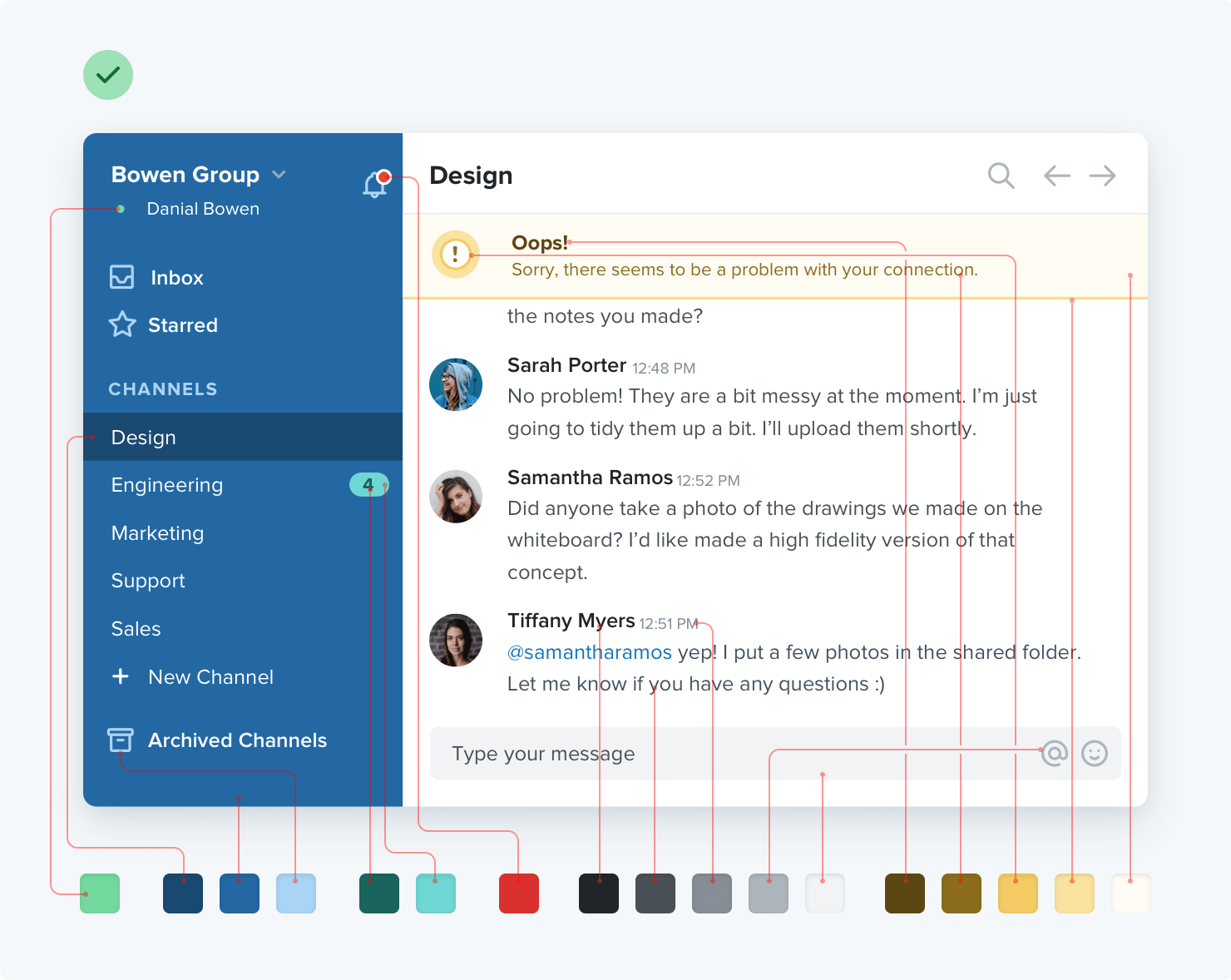

Instead, define a fixed set of shades up front that you can choose from as you work.

So how do you put together a palette like this anyways?

Choose the base color first

Start by picking a base color for the scale you want to create — the color in the middle that your lighter and darker shades are based on.

There's no real scientific way to do this, but for primary and accent colors, a good rule of thumb is to pick a shade that would work well as a button background.

It's important to note that there are no real rules here like "start at 50% lightness" or anything — every color behaves a bit differently, so you'll have to rely on your eyes for this one.

Finding the edges

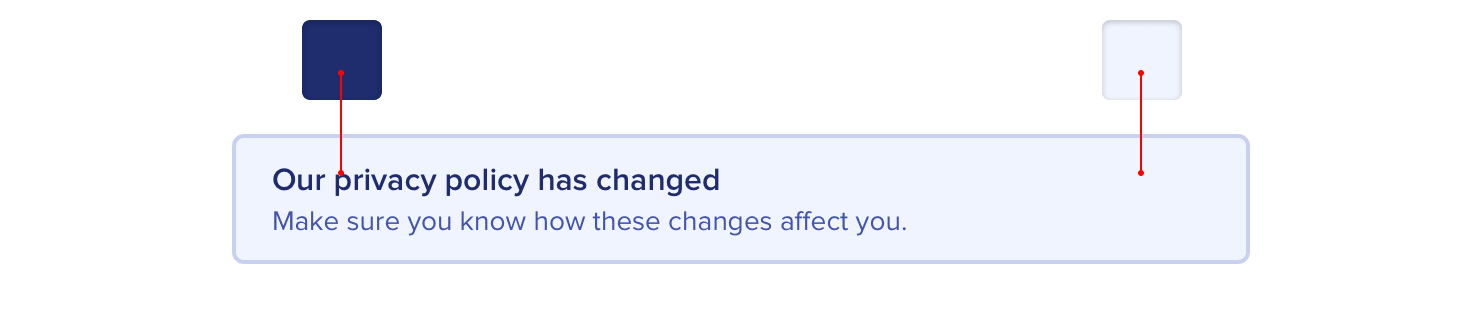

Next, pick your darkest shade and your lightest shade. There's no real science to this either, but it helps to think about where they will be used and choose them using that context.

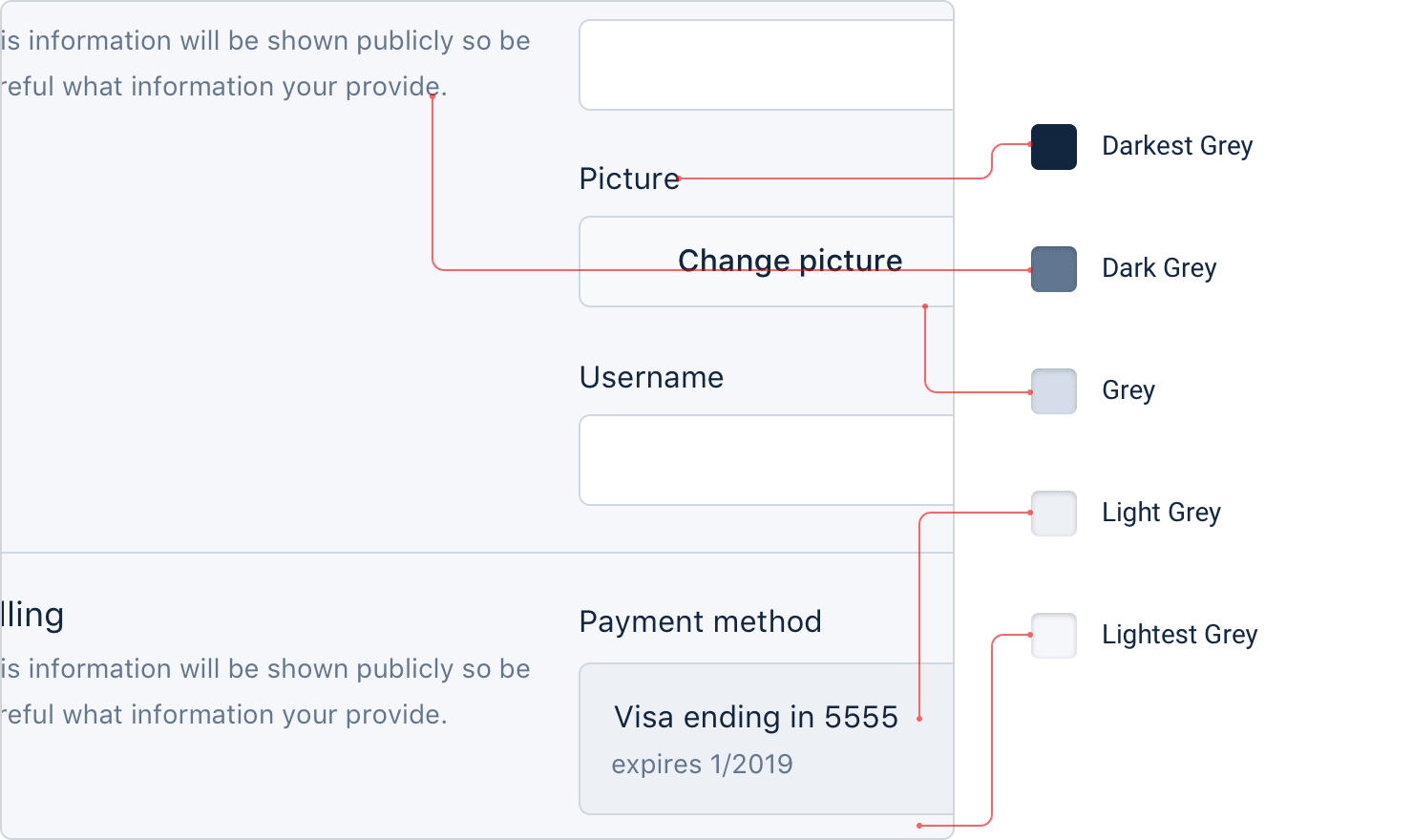

The darkest shade of a color is usually reserved for text, while the lightest shade might be used to tint the background of an element.

A simple alert component is a good example that combines both of these use cases, so it can be a great place to pick these colors.

Start with a color that matches the hue of your base color, and adjust the saturation and lightness until you're satisfied.

Filling in the gaps

Once you've got your base, darkest, and lightest shades, you just need to fill in the gaps in between them.

For most projects, you'll need at least 5 shades per color, and probably closer to 10 if you don't want to feel too constrained.

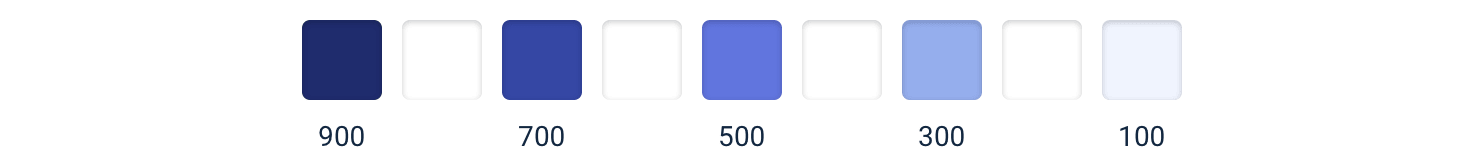

Nine is a great number because it's easy to divide and makes filling in the gaps a little more straightforward. Let's call our darkest shade 900, our base shade 500, and our lightest shade 100.

Start by picking shades 700 and 300, the ones right in the middle of the gaps. You want these shades to feel like the perfect compromise between the shades on either side.

This creates four more holes in the scale (800, 600, 400, and 200), which you can fill using the same approach.

You should end up with a pretty balanced set of colors that provide just enough options to accommodate your design ideas without feeling limiting.

What about greys?

With greys the base color isn't as important, but otherwise the process is the same. Start at the edges and fill in the gaps until you have what you need.

Pick your darkest grey by choosing a color for the darkest text in your project, and your lightest grey by choosing something that works well for a subtle off-white background.

It's not a science

As tempting as it is, you can't rely purely on math to craft the perfect color palette.

A systematic approach like the one described above is great to get you started, but don't be afraid to make little tweaks if you need to.

Once you actually start using your colors in your designs, it's almost inevitable that you'll want to tweak the saturation on a shade, or make a couple of shades lighter or darker. Trust your eyes, not the numbers.

Just try to avoid adding new shades too often if you can avoid it. If you're not dilligent about limiting your palette, you might as well have no color system at all.